When was the first time you really felt like a grown-up?

Growing up is a tough thing. We don’t leave childhood behind. It simply skips away, leaving us behind. And we find ourselves in the world of grown-ups. We certainly do gain quite a few things as adults, though: Responsibilities, duties, jobs, bills …

But at what point does it hit home that we’ve grown up? Is it a slow, dawning realization, or a thunderbolt to the head?

I first felt the pangs of adulthood when I moved to college. I had never lived apart from my parents before. Well, there was that one week in summer school, but that didn’t really count. Now, I was in the car with my parents going to a campus miles away from home and with the full knowledge that I wouldn’t be coming back with them.

The moment I made that realization was the moment that I knew things were Different™. There was no going back to childhood ways. I was an adult. I would be living as an adult. That made me a little excited, a lot nervous, and very, very giddy.

You ever have that dream where you’re in freefall? And your whole body tingles with such severe giddiness that you feel like it will overwhelm you? That’s how I felt when I arrived at my college. I was falling, falling, falling, all the way down. The only thing keeping me from curling up into a ball of panic was the certainty that the fall would end with me hitting the ground standing upright. Everything was in order, my room was rented, my classes were scheduled, and my parents were still just a phone call away. I wasn’t going to fall forever.

And so I grew up. No more childhood games, just the memories of them. Big adult games, like Studying for the Test, Learning to Budget and Managing My Own Bedtime. Adulthood was upon me.

Of course, once I graduated and entered the Real World, I realized that college wasn’t a very grown-up place after all, but that’s a story for another time.

***

Many thanks for visiting my blog. I post updates on my writing career, I muse over storytelling and fiction, and I reflect on the curious and wonderful things in life.

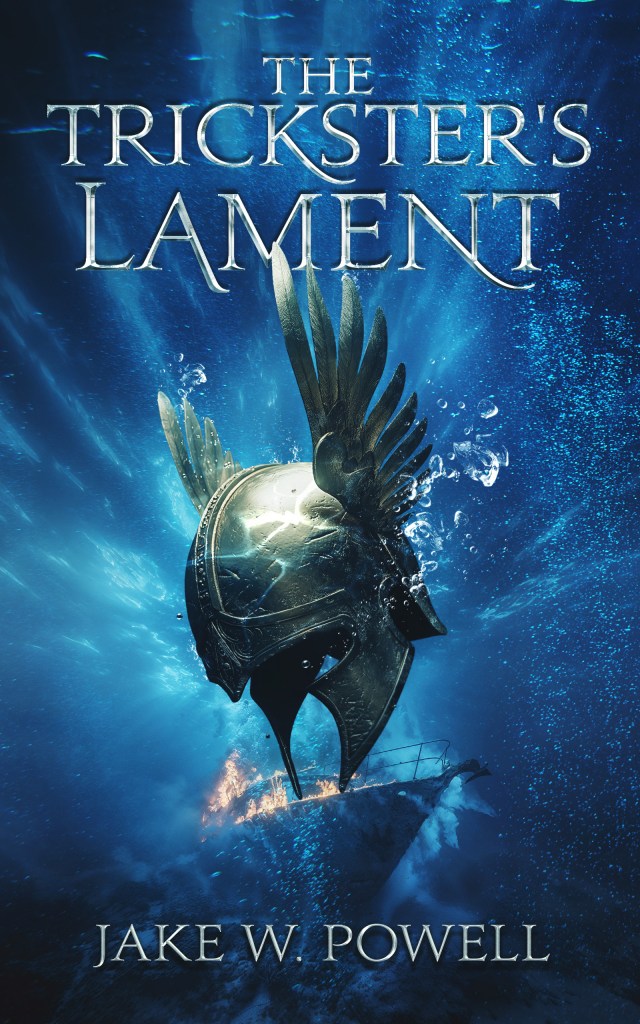

“Hermes is not having the best time. He walks a fine line, and his duty as messenger of Olympus weighs heavily on him. Being a god in the modern age means living in a world that no longer believes in gods. How much can one deity accomplish when no one respects him anymore? And why do his instincts tell him that he, the son of Zeus, is losing favor with his own family?

Tensions abound. The upstart Young Gods play dangerous games using entire cities as their boards. Formless monsters strike from the nighttime shadows, terrorizing hapless mortals. Agents of rival pantheons scheme to thwart Olympus’ designs. In the thick of it all, Hermes does what he does best: trick, lie, and cheat his way to victory.“