Fact is stranger than fiction, they say. And it’s true. But have you ever considered the inverse: Fiction is never stranger than fact.

No matter a writer’s imagination, no matter his ability to craft new worlds out of his own mind and populate it with characters who seem as real and unique as anyone you meet on the street, and no matter how engaging, grandiose, bizarre, or heartfelt the events portrayed in his work, he will never be able to surpass the parade of the unexpected that is world history.

History IS story. It’s right there in the word, isn’t it? And it’s real. Just think about that for a moment. Think about all the things you’ve read in the history books. Adventure. Romance. Mystery. Tragedy. War. Friendship. Triumph. Defeat. Despair. Hope. All of it is there, all of it waiting to be discovered by that one author seeking a mote of inspiration.

Where am I going with this? Just to say this: We writers have so much to draw from just by browsing the history section at our local library or bookstore. Heck, just go online. We live in the age of information. The World Wide Web contains everything. Try a quick surf of your hometown’s newspaper archives. Stories aplenty. Ideas in abundance.

And now I’m starting to think that there are so many tales in history that haven’t been given their due. Forgotten stories that need a time to shine. Eras and events that have been lost in the bustle of modern progress. Martin Scorsese’s Killers of the Flower Moon highlighted a time in Native American history that deserves more recognition. A terrible time, but one that should be known.

What else have we misplaced? What battles and victories waiting for their recognition? Unsung heroes waiting for their song to be written? Tragedies yet to be acknowledged? Villains who thought they got away with it?

Apologies, I’m just waxing poetical now. You get the idea. Writers don’t just write stories. We live at the tail end of the longest story ever written. All we have to do is look back a little ways for new tales from that saga to tell. Isn’t that a teensy bit amazing?

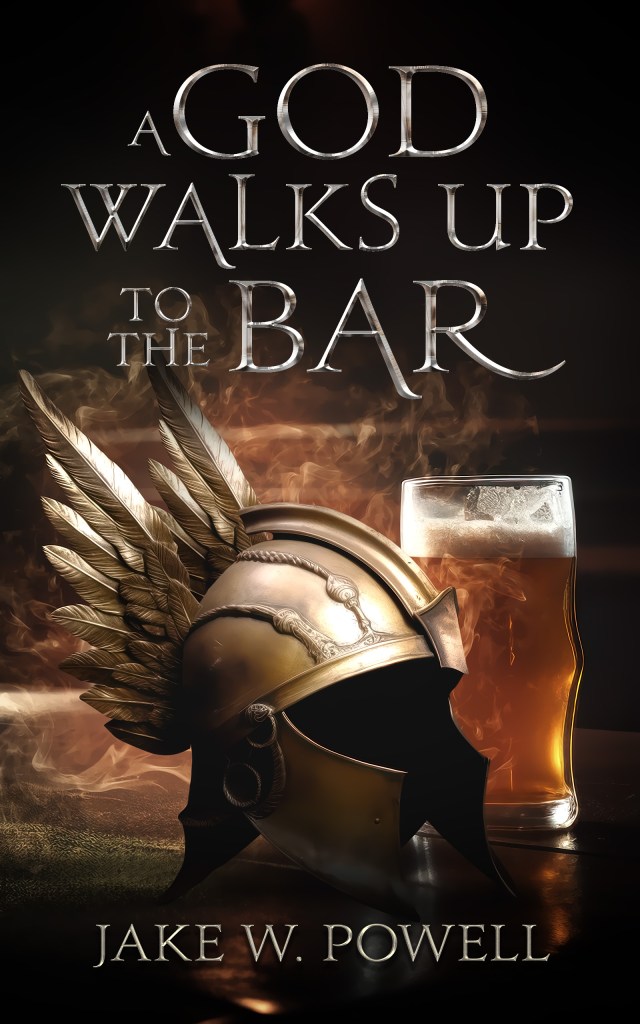

If you just so happen to be enjoying my blog, feel free to subscribe. I post updates on my writing career, I muse over storytelling and fiction, and I reflect on the curious and wonderful things in life.

Image: “Early printed vellum leaf” by Provenance Online Project; Licensed under CC0 1.0.