The story of the redeemed villain is a common and provocative trope in storytelling. It’s always fascinating to witness how a thoroughly evil and vile figure can turn around and repent of their ways. We like to see these tales play out and watch what happens next. It appeals to us.

Maybe the villain is likeable enough that we don’t want to see them die, or maybe we even see a little bit of ourselves in there, and hope that their redemption means there’s hope for us, too. Whatever the reason, a villain’s redemption is a major story beat, and should be treated as such. Which, in turn, means that writers should seriously consider it before going through with it. Is it the right move for the story? Is the villain truly redeemable, that is to say, is it a logical and fitting step in their growth as a character? Are they willing to seek redemption? Most importantly, can they be redeemed in a way that the audience finds natural and believable?

It’s easy to fall in love with a good villain and not want them to die. So, some writers just … give them an out. The villain evades consequences, sobs a few tears, gives a dramatic monologue, and skips on over to the side of good. And are welcomed with open arms. But is that how it would actually play out in the context of the world you’ve written? How bad is your bad guy? Did they blow up a planet, or just steal a few pies? If it’s the former, do you really expect them to be immediately welcomed and trusted by the heroes?

Don’t get me wrong, I’m not talking about a villain-hero team-up. Sometimes, good guy and bad guy have to work together, usually against a worse bad guy, but the villain remains clearly villainous, just currently motivated by shared interest. To be redeemed, a villain must be penitent. And to be penitent, a villain must truly feel remorse. And in feeling remorse, a villain must show a change in action and motivation.

A redemption arc is character development. The character will not be the same person at the end of it. Indeed, we writers should seriously consider this fact. If the villain was likeable because of their villainy, then redeeming them may in fact hurt them as a character. They’re no longer a villain. Will that take away what made them interesting and engaging?

On the other hand, you could have the villain redeemed through the classic act of self-sacrifice. It worked for Darth Vader, didn’t it? But, and hear me out, I think this is a bit of a cheat. Imagine how different things would have been for this classic movie villain if he had survived and had to stand trial before the people whose friends and family he had slaughtered. He would have to face his daughter Leia over the destruction of Alderaan. He would deliver himself into the hands of the Rebel Alliance he had hunted down for the whole trilogy. He’d have to live with the memories of his crimes. He’d have to do more than gasp a few words to his son as he lay dying to convince us he was truly changed. He would have to make his redemption stick. An interesting thought, no?

Redemption arcs are fascinating. They offer an incredible opportunity to explore facets of a character that usually aren’t. How and why does the villain do what they do? What would make them stop doing it? Can they stop? Do they have doubts? Do they value something greater than their current goals that they would give up their desires for? These are the sorts of questions that can help you figure out if your villain is a candidate for a moral turnaround.

The most important question to ask is: Does it serve the story? We are talking about fictional characters, after all. They’re not real people, they’re figures in a narrative that we as writers have the responsibility and privilege to manage and direct. Redemption and repentance in real life is quite another thing entirely, even if they do inspire our work. Real life is fuzzy. We can’t truly know other people’s motivations. But we can know exactly what motivates the characters we write, and so we can answer this question with confidence: Can my villain stop being bad?

If you just so happen to be enjoying my blog, feel free to subscribe. I post updates on my writing career, I muse over storytelling and fiction, and I reflect on the curious and wonderful things in life.

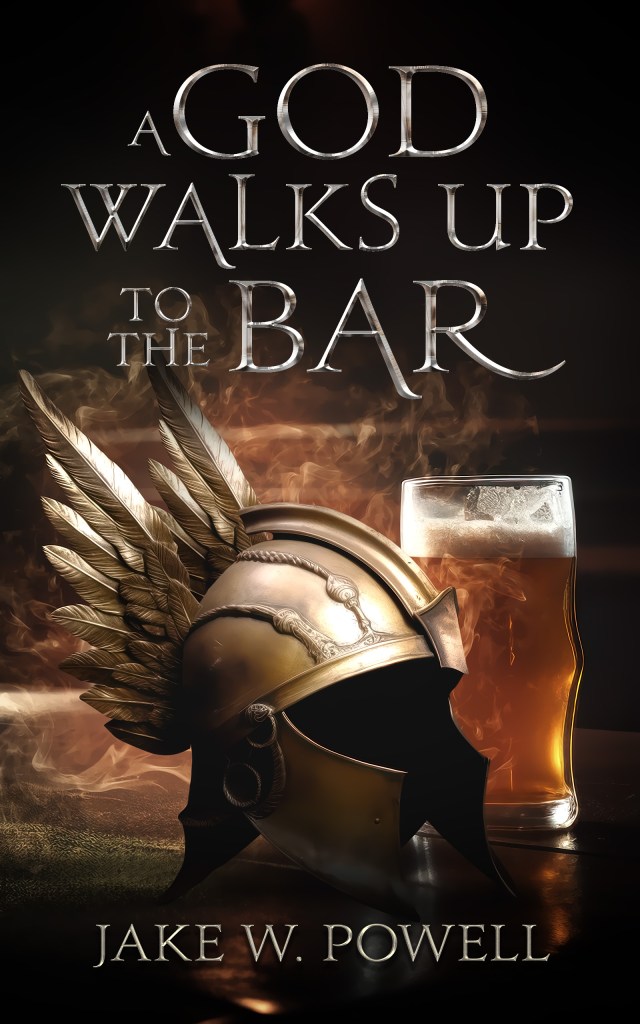

My first book, A God Walks up to the Bar, is available on Amazon.com. Witness the modern day adventures of the Greek god Hermes in a world much like our own – and with demigods, vampires, nymphs, ogres, and magic. The myths never went away, they just learned to move on with the times. It’s a tough job, being a god!

Image Source: “THE Supervillain’s Lair” by nicknormal; Licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.